The effectiveness of computer assisted TKA compared with traditional TKA.

It is well known that total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a successful and widely practiced treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee, both in terms of alleviating pain and enhancing function1. Implant malalignment and malposition are linked to poorer function and/or greater revision rates, whereas adequate alignment and good component location at the time of TKA increase TKA survival. Restoration of the mechanical axis by axial alignment of the limb is crucial. It is believed that a mechanical axis lying within a varus/valgus range of 3 degrees is linked to a more favorable result.

Traditional total knee arthroplasty has been performed for a very long time. In up to 30% of instances, the post-operative alignment of the limb was found to exceed the range of 3°, despite the technique’s widespread use and global success. This indicates that around 30% of individuals undergoing TKA with traditional techniques are at risk for malposition, maladjustment, and possibly revision surgery.

Peterson and Engh reported the radiological outcomes of 50 primary TKAs done using the standard approach in their study. In their study, 26% of TKAs failed to achieve a varus/valgus alignment within 3 degrees. Similarly, Mahaluxmivala’s analysis of 673 TKA cases using traditional methods led us to the conclusion that a 3 degrees varus/valgus was present in 25% of cases, regardless of the surgeon’s years of expertise2.

In addition, when TKA is done in hospitals with a lesser volume (hospital volume 25–50 TKAs per year), a greater TKA revision rate after 5 to 8 years and increased complications have been recorded3. Thus, improving revision rates and decreasing component malposition has been the focus of recent studies.

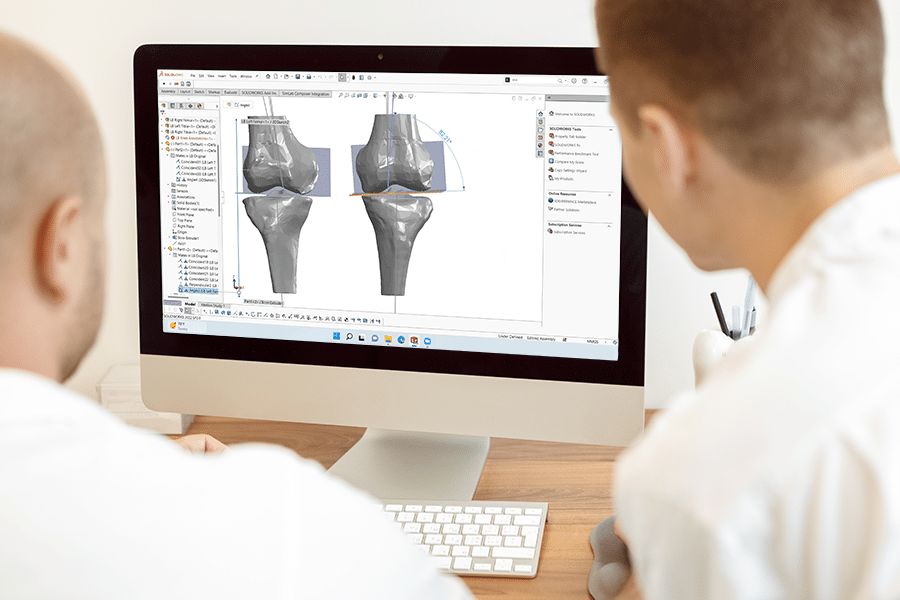

The development of computer-assisted navigation systems has increased the precision of TKA component alignment. Navigated TKA was initially conducted in 1997, and its application and technology have significantly progressed since then4. Navigated TKA has been regarded as a valuable approach for TKA patients with extraarticular deformity. Navigated TKA combines computer-assisted orthopedic surgery with traditional TKA in an effort to enhance the clinical, radiological, and functional scores of patients having TKA by eliminating radiographic outliers.

Current studies are being carried out to see which of the two methods of TKA offers a better outcome. Is it time that preference should be given to the computer based navigated TKR and conventional methods should take a backseat?

Navigated TKA proponents have asserted that these techniques may enhance functional scores, alignment, revision rates, and survival in TKA. Reduced radiographic outliers in coronal and sagittal plane alignment, improved component axial rotation accuracy, improved flexion-extension gap and ligament balancing, comparable operating times once experience is gained, acceptable costs, low complication rates, reasonable learning curves, equal or improved functional scores, and the potential for increased TKA implant survival are all reasons to choose navigated TKA over conventional TKA. Additionally, even though a lot of these guided TKA studies do demonstrate improvement in radiographic outliers, they accurately point out that these gains have not yet been transferred to better knee function, quality of life, or implant longevity5. The specific difficulties connected with navigated TKA as well as the increased cost and length of the procedure call into question the computer guided TKA’s cost-benefit6.

However, various studies have shown a wide range of results when it comes to functional significance and quality of life of the patients when it comes to comparing the two methods.

Research conducted by Mielke in 2001 showed that with a navigation system, there was a propensity for a better femorotibial axis. However, this did not achieve statistical significance. A similar study conducted by Jenny and Boeri discovered no significant difference between computer-assisted TKA and the conventional approach in the postoperative period. In their investigation, a mechanical axis of 3 degrees varus/valgus was reached in 83% of patients utilizing a navigation system and in 78% of patients using a standard technique.

Conversely, a multicenter study conducted by Jenny and Mielke7 showed that with computer-assisted surgery, a much superior post-operative axis was established in 555 TKAs. In this study, 88% of patients achieved an axis of 3° varus/valgus alignment, compared to 72% in the conventional group.

Despite the controversial results, it is established that with guided TKA, it may be possible to reduce mechanical axis malalignment outliers; however, the costs, greater operating time, increased training, risk for new and increased problems, cast doubt on its function in routine TKA. Patients with extraarticular deformity or retained implants and hardware that exclude the use of conventional extra- or intramedullary alignment guides are candidates for guided TKA. However, calling for the conventional methods to be scraped off will be a very early and premature call. To adequately evaluate the medium- and long-term outcomes of guided TKA, future clinical studies should be structured to follow patients at the short and medium term to record improved clinical function and at the long term to determine if lower revision rates are attained.

Computer assisted technology will only continue to get more accurate and more efficient with time. Kinomatic is using computer software for the entirety of the surgical planning process, from segmentation to final surgical plan. We believe this offers patients the most accurate version of a joint replacement that can currently be achieved. To learn more about how Kinomatic’s approach to total joint replacements, click this link.

References

1. Bäthis, H., et al. “Alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a comparison of computer-assisted surgery with the conventional technique.” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume 86.5 (2004): 682-687.

2. Mahaluxmivala, J., et al. “The effect of surgeon experience on component positioning in 673 Press Fit Condylar posterior cruciate-sacrificing total knee arthroplasties.” The Journal of arthroplasty 16.5 (2001): 635-640.

3. Ohmann, Christian, et al. “Two short-term outcomes after instituting a national regulation regarding minimum procedural volumes for total knee replacement.” JBJS 92.3 (2010): 629-638.

4. Delp, Scott L., et al. “Computer assisted knee replacement.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (1976-2007) 354 (1998): 49-56.

5. Ishida, Kazunari, et al. “Mid-term outcomes of computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 19.7 (2011): 1107-1112.

6. Tigani, D., et al. “Computer Assisted Surgery in Total Knee Arthroplasty.” Current Rheumatology Reviews 6.2 (2010): 151-159.7. Kluge, Wolfram H. “(iv) Computer-assisted knee replacement techniques.” Current Orthopaedics 21.3 (2007): 200-206.